August 08, 2022

CFAR Director's Update

Image

Dear CFAR community,

I wanted to provide you all with an update on the monkeypox outbreak unfolding globally as well as a 1-week reminder of our HIV-Monkeypox CFAR grants (due August 15, 2022).

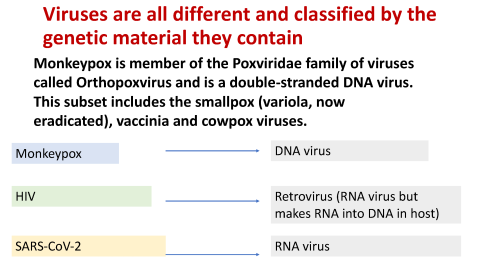

Remind me of the virus that causes monkeypox

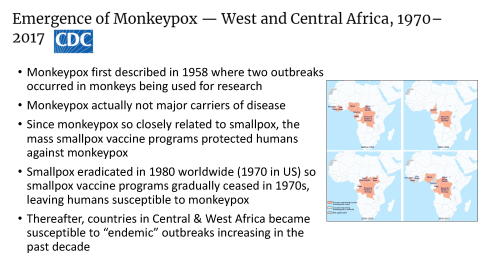

Monkeypox is a member of the Poxviridae family of viruses called Orthopoxvirus and is a double-stranded DNA virus. This subset includes the smallpox (variola), vaccinia and cowpox viruses. The name “monkeypox” (which many – including me- should be changed) comes from the first documented cases of the illness in animals in 1958, when two outbreaks occurred in monkeys being used for research. However, monkeys are actually not major carriers of the disease.

Image

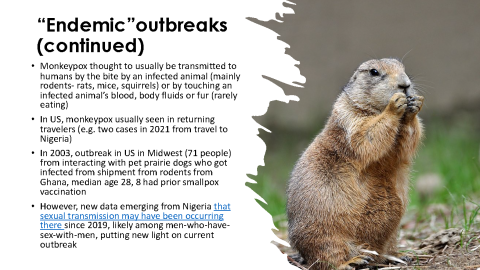

How is it spread, where was it endemic, and is there any new information coming out of Africa that can spread light on the current outbreak?

Prior to this outbreak, monkeypox was thought to be usually transmitted to humans by the bite by an infected animal (mainly rodents, such as rats, mice and squirrels), or by touching an infected animal’s blood, body fluids or fur. It's also possible to catch the disease by eating meat from an infected animal that is undercooked. However, as this outbreak has emerged, there have been questions raised whether monkeypox in Nigeria was actually spreading through sexual contact since 2017, with scientists in the region (Nigeria) reporting likely men-who-have-sex-with-men spread (mentioned in this PLOS ONE article about the Nigeria outbreak 2019). It is possible that criminalization of LGTBQ behavior in some African countries has confounded whether there was sexual transmission there due to lack of reporting. Prior this current outbreak, this disease was usually limited to central and West Africa or to travelers who have recently come back from these regions. For example, prior to current outbreak the last case in the US was identified on July 15, 2021 in a US resident who had traveled from Nigeria to the US on two commercial flights. Contact tracing revealed 200 contacts and none developed symptoms. There was another imported monkeypox case in November 2021 in the United States (in Maryland) in a person who had recently traveled to Nigeria as well. The last major event in the US related to monkeypox prior to that was an outbreak in 2003 related to pet prairie dogs here getting infected by rodents No instances of monkeypox infection in that particular outbreak seemed to occur from person-to-person contact. We will discuss the protective efficacy of the smallpox vaccine against monkeypox (or what is known about it) in a later section, but in the 71 person outbreak from the infected prairie dogs, the median age was 28 (so too young to have had smallpox vaccination) but 8 people who were infected with monkeypox had been vaccinated for smallpox before.

Image

Image

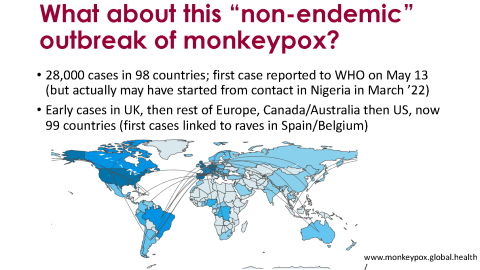

What is the latest epidemiology of the current outbreak worldwide and in the United States?

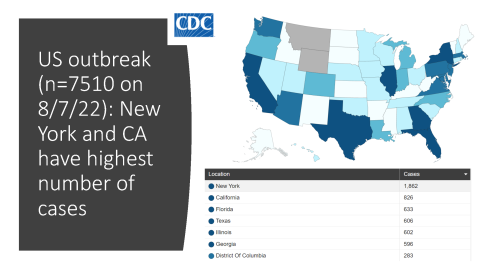

The best website I have found to track data about the current monkeypox outbreak is monkeypox.global.health. Although the first case in a gay man was reported to the WHO on May 13, 2022, there are now questions whether the first cases for this particular outbreak were in Nigeria. Now, from May 13 to August 7, 2022, over 28,000 cases have been reported in 99 countries, mainly among men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM). In the United States (which has the highest number of cases in the world), there are 7510 cases with the states with the highest number of cases being New York followed by California.

Image

Image

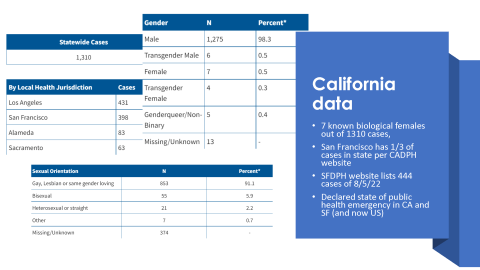

What is the epidemiology of the outbreak in California and San Francisco?

In California, there are cases reported as of August 7, with one-third of those cases being in San Francisco. The San Francisco DPH lists 444 cases as of August 5, 2022. The California Department of Public Health has a nice breakdown of demographics. Of 1310 cases, only 7 are in biological females and the outbreak consistently seems to be mainly in men-who-have-sex-with-men.

Image

How is monkeypox being transmitted in this current outbreak?

The main route of transmission seems to be close skin-to-skin contact or close respiratory contact occurring during sexual activity. Although monkeypox has been found in semen (which is why counseling on condoms could be effective), the most likely route still seems to be the close contact during sex. Transmission via droplet respiratory particles can occur with prolonged face-to-face contact, which puts household members and other close contacts of active cases at greater risk. There have two cases of monkeypox among young children in the US, likely from contact with lesions from an infected parent in the household but cases in children are very rare and resources should be directed towards the community most affected (and within whose social networks this is spreading): men-who-have-sex-with-men

What are the symptoms of monkeypox?

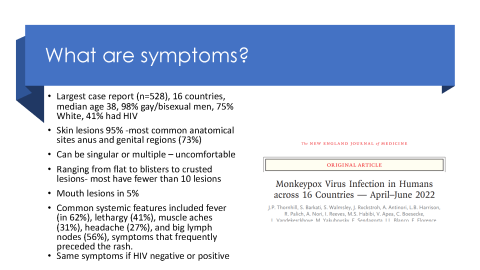

In terms of the main clinical symptoms, an important case series was published in the NEJM on July 21 which describes the main clinical features of monkeypox in this outbreak. Among 528 cases diagnosed between April 27 and June 24, 2022, at 43 sites in 16 countries, 98% of the persons with infection were gay or bisexual men, 75% were White, and 41% had HIV; the median age was 38 years. Transmission was suspected to have occurred through sexual activity in 95% of the persons with infection. Skin lesions were noted in 95% of individuals with the most common anatomical sites being the anogenital area (73%); the trunk, arms, or legs (55%); the face (25%); and the palms and soles (10%). A wide spectrum of skin lesions was seen, including macular (flat), pustular, vesicular (blisters), and crusted lesions, and lesions in multiple phases were present simultaneously. The number of lesions varied widely, with most having fewer than 10 lesions and 10% having only a single genital ulcer (which can be confused for another sexually transmitted infection, STI). Mucosal lesions were reported in 41% of individuals and among those with anorectal lesions, the involvement was associated pain, proctitis, tenesmus, or diarrhea (or a combination of these symptoms). Oropharyngeal symptoms were reported as the initial symptoms in 5% of the case series, with symptoms that included pharyngitis, odynophagia (pain when swallowing), epiglottitis, and oral or tonsillar lesions. Common systemic features included fever (in 62%), lethargy (41%), myalgia (31%), headache (27%), and lymphadenopathy (56%), symptoms that frequently preceded the rash. Of importance is that the clinical presentation was similar among persons with HIV infection and those without HIV infection.

Image

Image

What are treatments?

Previously, there were no specific treatment for a monkeypox virus infection and patients are generally managed with supportive care and symptomatic treatment. However, for those with disseminated lesions or lesions which are in very sensitive places, the CDC is offering tecovirimat. The evidence is still being gathered on tecovirimat or TPOXX in terms of effectiveness. In terms of what we know so far, there have only been non-randomized, unblinded investigation of the efficacy of tecovirimat against monkeypox infections in humans and that data is encouraging. This monograph summarizes some of the animal studies of tecovirimat against smallpox and this Lancet article on August 1, 2022summarizes some of the observational data of tecovirimat against monkeypox; there are only case studies presented but they are all encouraging as has been the anecdotal reports on the use of tecovirimat from our clinic according to Vivek and John Szumowski

The US CDC currently recommends tecovirimat be used under an EA-IND for 14 days for patients with severe monkeypox infection or those who are at risk for severe monkeypox infection and there is an IV formulation available for inpatient use. The ACTG is launching a clinical trial (randomized) to look at tecovirimat for its safety and efficacy against monkeypox (placebo-controlled) under NIAID.

How effective is the vaccine and where are our current vaccine supplies?

One vaccine, JYNNEOSTM (also known as Imvamune or Imvanex or Jynneos), has been licensed in the United States to prevent monkeypox and smallpox. On June 1, the CDC updated its recommendations to say that Jynneos is the preferred post-exposure prophylaxis for monkeypox here in the United States- this would be for close contacts (including health care workers) and laboratory workers. JYNNEOS™ is usually administered as a series of 2 injections, 4 weeks apart. People who have received smallpox vaccine in the past might only need 1 dose. Given that this is endemic and at Africa’s very reasonable concern that this is only being paid attention to in the context of this current outbreak, the World Health Organization declared monkeypox a public health emergency of international concern on July 23 to help ramp up supplies for both non-African and African countries.

In terms of the effectiveness of the smallpox vaccine for monkeypox, no one knows for sure although the fact that monkeypox started emerging in West and Central Africa in outbreaks after the smallpox vaccination campaign ceased is certainly convincing that the smallpox vaccine (ACM2000 was the most common one used in the past) covers monkeypox. A Retrospective analysis published in 1988 examined whether a smallpox vaccine could prevent monkeypox by tracking the household contacts of 209 people infected with monkeypox in Zaire in the early 1980s. Those with scars from previous smallpox vaccination (70%) were 85% less likely to be infected. The vaccine seemed to be 89% effective at protecting contacts outside the household from infection. The study design is obviously limited and this current monkeypox outbreak and the mass Jynneos vaccine campaign will give us better data. However, we don’t have a designated monkeypox vaccine yet and in the interest of a public health emergency, providing immunity with the closest vaccine candidate we have is certainly indicated.

In terms of vaccine supplies, this has been a source of frustration for all of us with many advocating for immediate vaccine production in June (I wrote this piece for the Atlantic that month saying we are underreacting). You all likely heard of the delay in getting vaccines from Denmark due to FDA sluggishness and this is not the place to write about problems in our response but we all very much hope we can have ample supply of vaccine soon. Ward 86 has been grateful to SFDPH for prioritization of the vaccine for MSM and people with HIV (many of whom are seen in our clinic on campus).

How to diagnose monkeypox?

Monkeypox can be tentatively diagnosed if the characteristic skin lesions are present, or if other symptoms consistent (e.g. look for the more characteristic symptom of lymphadenopathy with monkeypox) with the disease are seen during an outbreak. The diagnosis takes unroofing of a lesion and then sending for testing using Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) which is the preferred laboratory test given its accuracy and sensitivity. Where feasible, biopsy is an option.

What is CFAR doing for HIV and monkeypox?

The CFAR Monkeypox Rapid Response Pilot Grant Program seeks to support rapid response research at UCSF focused on the emerging Monkeypox epidemic in the context of HIV. Many aspects of the epidemiology and viral pathogenesis of monkeypox are not fully understood. We seek to support research efforts to better understand monkeypox in the context of HIV infection or prevention. Projects must be within NIH’s HIV/AIDS research high or medium priority areas and clearly linked to HIV in order to be eligible for CFAR funding. Clinical trials are not allowed.

We have now moved the grant deadline up to August 15 (1 week from today) to allow more time for submission.

Thanks all,

Monica